But Write the Elevator Pitch if You Really Want to Become Unhinged

I was an Indian girl whose conservative Christian parents were giddily arranging my marriage while I became faint at the thought of telling them I was pregnant by my secret American boyfriend.

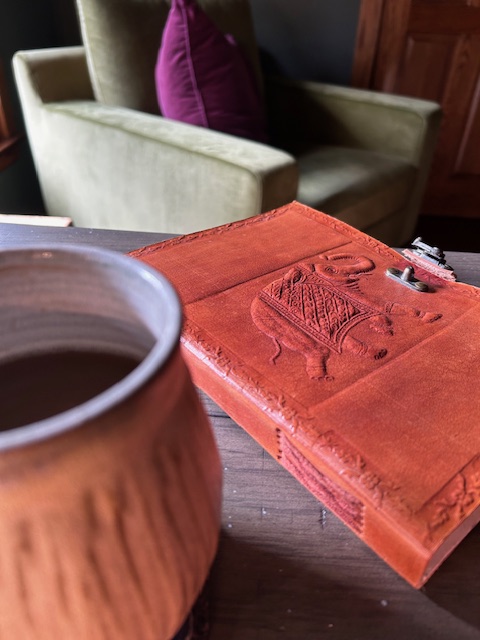

This is my elevator pitch, one funky little sentence that took almost as long to write as the book itself. I had to conjure it up, press it down and have it sizzle and simmer to near surgical precision. I had to make it gripping, informative, fast-moving. And I knew, even if no one else said it in all the articles about proposal writing I pored through, it had to be the rawest thing I wrote.

It was about throwing everyone, including myself, under the bus. It was a loaded nutshell. It was the one place I couldn’t mask the big stuff, no matter how poetically and metaphorically I wrote the book.

I tried to protect them, my parents, who were scared immigrants in an unkind place. No one told them about the oppressive systems that were snugly in place and under the guise of, oh this is just how things are in America. However, these systems kept them from their dreams and dismissed their efforts. One look at their medium brown skin, their ethnic clothes, and their molasses thick accents, and they were quickly thrown aside.

All that came streaming down onto me like a waterfall of sorrow pooling into a raging sea. It became a melancholy childhood cloaked in conforming, the reckless teenage years and the making of generational immigrant trauma. It poured into me and clashed, because my American-infused Indian customs didn’t align with their rigid Indian rules.

And awesome for me, I got to write about all of it. I say this with only slight sarcasm, because it has been one of the most painfully satisfying things I’ve done. But it sure was hard. Ironically too, the difficult part was arriving at the place of being the realest I could possibly be with myself. Once there, it didn’t feel so torturous anymore. It felt like freedom. It felt a little like delusion too, like telling myself that my parents and whoever else would understand my perspective. I told myself they would have empathy for my telling of what we all remember, likely in different ways sometimes.

And to do that, I had to understand what the core of the story was. I had to muddle through the memories, eek through the emotions, sift through what didn’t need telling and come to a place of knowing where the heart of the story lived.

And that led me to the elevator pitch, a kinda run on sentence that captured the root and all the real of my story. But I guess that’s memoir. It’s keeps running on, digs up those memories in the corners of our minds and catapults them into deeper wells of recollections, pain and maybe even a little joy.